As a photographer, it’s easy to get hung up on the technical details of light, composition, settings, etc. and completely forget to ask meaningful questions about your subject and the environment you’re photographing in. I get it! In a world dominated by social media and checklist culture, there is a tendency to click it, forget it, and move on to the next one.

It’s often said that a key to creating great photographs is doing your research. But what this typically refers to are logistical tasks like taking the time to scout a location, planning for the right light, locating a compelling subject, and the list goes on and on. Of course, all these aspects of planning and execution are important to creating great images, but I want to make the case for also including a different kind of research in photography. Slowing down enough to be curious and doing the kind of research that deepens your understanding of subject and place has the potential to totally transform your photography!

In Favor of Research

Most of us working in the photography world have, at some point in our journey, found ourselves also working in other fields. For me, that other field has been academia. Over the last four years, I’ve slowly pursued a Ph.D. in international studies while simultaneously making the move into full-time photography. Because of this, I often find myself straddling two worlds – one foot in the analytical world of academia and the other firmly planted in the world of visual art.

Balancing two completely different realms of life can get complicated, and it’s inevitable that aspects of each bleed over and influence the other resulting in some unexpected benefits. One thing that this double life has taught me is the value of good research. While this skill is the presumed default of academia, it turns out that it can be truly transformative for photography as well.

You see, in academia, high-level research often begins with asking questions followed by a dogged pursuit of that curiosity to peel back the surface layer and uncover hidden relationships, overlooked details, and a deep understanding of the issue at hand.

While the application of this approach to conservation photography has long been the norm, it’s something that I’ve rarely heard discussed in traditional landscape photography circles.

Instead, through the magic of social media, we are fed an endless barrage of epic sunset ‘bangers’ of questionable realism and pretty picture after pretty picture with very little meaningful context. Most of the research generating these images involves a planning app and perhaps a bit of scouting (all of which is important to be sure) but doesn’t go much deeper than that. When the research behind an image doesn’t go more than surface deep, it’s not a surprise that we walk away with pictures that may be stunning but lack meaningful impact.

Photography + Research in Practice

So, what does applying research to landscape photography look like in practice? It all starts with asking questions! Imagine yourself walking along a wooded trail surrounded by old growth hardwoods and the sound of songbirds hidden in the canopy. At the end of the trail, there’s a beautiful waterfall. I don’t think anyone would blame you if you started by finding a composition and then began calculating your shutter speed to capture the scene before returning to your vehicle to head to the next location. I’ve certainly done plenty of this ‘run and gun’ photography myself after all!

But, what if you took a different approach? What if you gave yourself time to be curious and ask questions about the environment you found yourself in?

What makes this place unique? Why do some plants only grow behind the waterfall while others only grow downstream? How has the spray of the falls created a miniature ecosystem within its reach? The green moss is pretty, but what is its environmental role? If you had asked these questions, would you photograph the scene differently? If you had known that deforestation is one of the region’s greatest threats, would you have only photographed the waterfall? Would you look at this place differently if you found all these answers and then returned to photograph it again?

The reality is that committing yourself to deeply researching and understanding your subject will require you to push up your nerd glasses and get to work! You’ll probably spend a lot of time suffering through the dry language of scientific publications and trying not to go mad while interpreting tables of fancy data.

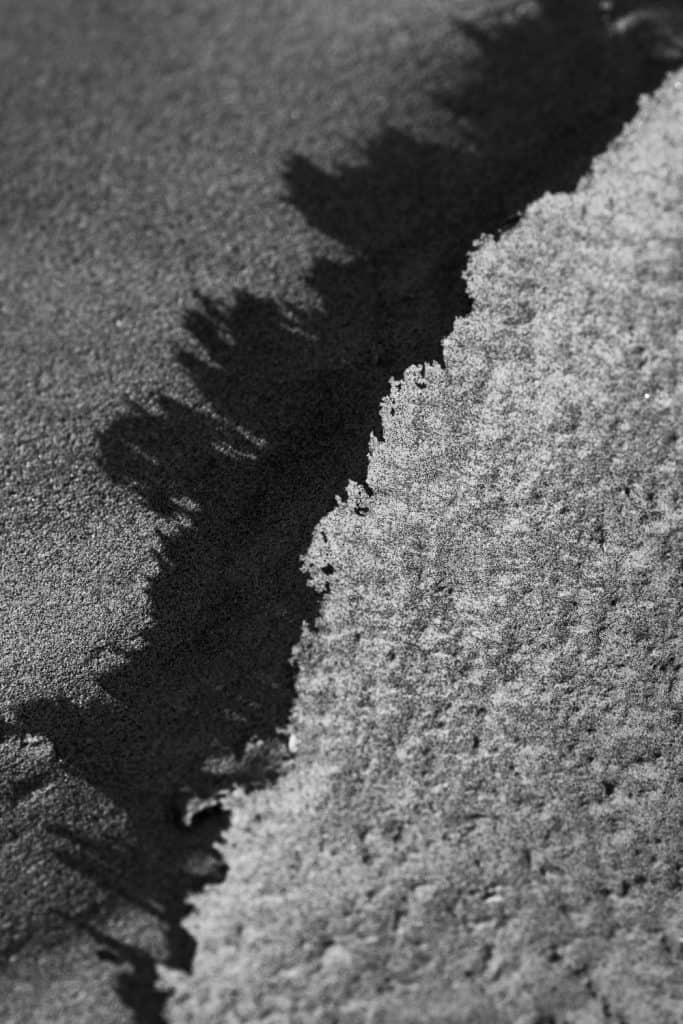

One time I got way too curious about the natural crusts on certain sand dunes and ended up down a multi-day rabbit hole learning new terms like ‘dune mobility’, ‘leeward’, and ‘abiotic crust dynamics’ all of which served to deepen my own interest and shape my photographic approach to a subject that would be otherwise pretty mundane.

In another example, I used academic-style research to help create better photographs of a location I was creatively struggling with. The Suwannee River and the amazing ecosystem surrounding it is near and dear to my heart, but this impenetrable forest of razor-sharp palmettos and entangled oak trees is incredibly difficult to photograph. In this chaotic environment, it was hard to know where to begin and, after numerous visits, I still wasn’t proud of my images. It was time to take a different approach and I quickly found myself chasing my own curiosity. Why was the water so dark? What made the area along the river so different from everything around it? What’s the relationship between the Spanish moss and its host tree? Does the river face any environmental threats?

After reading dozens of academic articles on a variety of subjects ranging from water flow studies to ornithology (bird) surveys to a completely bizarre fern experiment, I finally found a way to see the Suwannee River with new eyes. I learned that the Suwannee is a rare blackwater river that derives its color from tannins and, despite the name and appearance, in the right light the water is actually red. I learned the Suwannee is one of the longest undammed rivers in the U.S., so seasonal floods have shaped the ecosystem around the river into something entirely unique from its surroundings. I also learned that the small unassuming ferns I’d walked past so many times are actually resurrection ferns and that this little plant had unique and incredible adaptations allowing it to survive up to 100 years of drought. And apparently, the mercilessly sharp palmettos that I had repeatedly struggled against had also protected the live oak forest by keeping loggers at bay.

With a new appreciation of this unique place and the relationships within it, I returned to the Suwannee River armed with the information needed to create better photos. Although the photo series is still a work in progress, I came away with images that I think helped tell the story of the Suwannee.

You see, a deep understanding of subject and place is truly empowering. It takes you beyond simply creating pretty pictures to uncover hidden relationships between your subject, the elements of your scene, and the ecosystems they inhabit.

Why Digging Deeper Matters

A common refrain in the landscape photography community is, “I want to do more than just take pretty pictures.” At its core, a deep understanding is the foundation of creating meaningful images with impact, and it all starts with asking questions and doing your research. When you research your subject to gain a better understanding of environmental factors, conservation issues, and natural behaviors and relationships, you’ll take more than just beautiful photos – you’ll create photos that actually matter!

The bottom line is that it’s best to know it if you really want to show it. Sure, there’s nothing wrong with taking pretty pictures. I certainly create my fair share of images that are pretty and don’t have research behind them. But when I want to create images with meaning or a project with impact the truth is that you really have to know your subject to best be able to show your subject.

While the phase “knowledge is power” may be cliché, in the case of deeply researching the subjects you photograph, it is a truth that’s impossible to avoid. When you allow yourself space to be curious and then pursue that curiosity to truly learn about your subject, that’s when you have the power to move beyond ‘pretty pictures’ to tell a meaningful story, educate yourself and others, and become a real advocate for the places you love.