If you ask a photographer what kind of images he or she makes, the answer most commonly refers to a list of divergent subjects.

Over the years, I have seen evidence of the camera’s seductive power in student work. Most of us have diverse visual interests and are naturally pulled towards many subjects. This wouldn’t be anything to worry about except that a broad focus often leads to a less than an optimal portfolio without focus. Certainly, the world is full of wonders to photograph, but how many of us have the time to take every branch in the road? The hectic pace of our lives, and the expediency of clicking the shutter, conspires to distract us!

In my experience of teaching photography for the past forty years and reviewing portfolios, I have not often seen work presented in a tightly edited and conceptually concise manner. In recent years, through the process of teaching an online course, I have found a great way to improve your photography and give it more focus – by determining the major themes within your photo library, and developing refined and concise portfolios of those themes that inspire you the most.

My teaching experience tells me that many photographers, at all levels, can benefit from this more focused approach to creating, organizing, and marketing their imagery. The first phase in this process is to determine what themes already exist in your photographs. After discovering which of those that are the most promising, the next step is to edit the images into portfolios that showcase your best work.

One theme I have pursued since I started making images 35 years ago is patterns in Nature. In fact, my photographs were used to illustrate the subject in a book entitled By Nature’s Design.

Although I photographed many new images for the book, my files contained many previously made images that reflect my fascination with the subject. It is a theme I continue to pursue today: By Nature’s Design Portfolio.

It is important to consider what subjects really matter to you, themes about which you are most passionate. The subject can be broad, such as forests or as narrow as aspen, but the important thing is to focus on a theme, and to photograph with the idea of creating a portfolio. In my definition, a portfolio can take many forms and potential uses- a portfolio box of fine prints, a book, a web gallery, or perhaps an actual gallery exhibit.

When working on a student’s critique, I often find a few good images mixed in with many lesser ones. The overall impression is less than strong, the quality level lowered by the weaker ones. When I pull out the weaker images, then set aside the best ones to define a stronger portfolio, the photographer instantly becomes a better photographer! Even when setting aside only two or three “best” images, good editing elevates the photographer’s sense of his or her achievement and ability. It can be a positive experience. If you don’t think you are a tough enough editor (yet!), then a workshop that includes critique sessions with an experienced pro will surely help. It is difficult to be brutal with your own work. Maybe if you imagine a workshop instructor looking over your shoulder as you edit, you will be more selective!

Your project could last just a few months, or involve a lifetime of work. The most enduring theme for me is the one I developed over two decades, and published in book form – Landscapes of the Spirit. Although the book has been out of print for many years, I released an e-book version – Landscapes of the Spirit – Digital Edition.

There are two main requirements for building a strong portfolio. First, there must be a coherent theme. For example, you could pick a topic of landscapes that relate to water. Possible images could include waterfalls, rivers, lakes, or the ocean.

The second criterion is that there should be no one image that is of lesser quality than another. Remember that, in any situation where you show your work, excellent photographs are diluted by the average photos that you might use to “fill out” your presentation. The overall impression of your photography is reduced. I wish that more photographic instruction emphasized the importance of editing.

The next step is to go through your files to find your very best “water landscapes,” or whichever theme you’ve chosen. If you adhere to my second premise, you will find the editing difficult! Being self-critical is critical! Don’t be surprised if you discover only a few images that are of equally high quality. The ultimate editor is you, the artist, but you may find it valuable to have your work evaluated by other, more experienced photographers, such as a workshop instructor. This “second opinion” approach will either confirm or force you to reconsider the level of your imagery.

You should now have the foundation for your portfolio, be it two or twenty images, and a baseline from which to measure your progress. When you continue to photograph for the collection, your planning, exploration, and image-making are concentrated on the theme. As you refine and add to your theme, consider the balance and coherence in terms of a variety of lighting, compositional style, scale, and creative perspective.

New images are compared to your standards of excellence and can be added to the portfolio if they measure up. Over time, some new photos might replace the original images as the overall quality of the portfolio is elevated. Those photographs that endure that still excite you remain in the portfolio. By evaluating this collection of premier images, you will often see and be rewarded by your progress.

How many photographs should be included in a portfolio? The size of a portfolio depends on the mode of presentation and the audience. If you are creating a book, submitting to a publisher, or self-printing, the need for at least 40-50 excellent images makes sense to me. If you are creating a box of fine art prints, either for yourself or to present to a gallery, I recommend a smaller number, say 20-30 photographs.

You must do your research by asking how many photographs the publisher, gallery director, or editor wants to see. By checking for submissions guidelines, you will also learn what forms of presentation are acceptable.

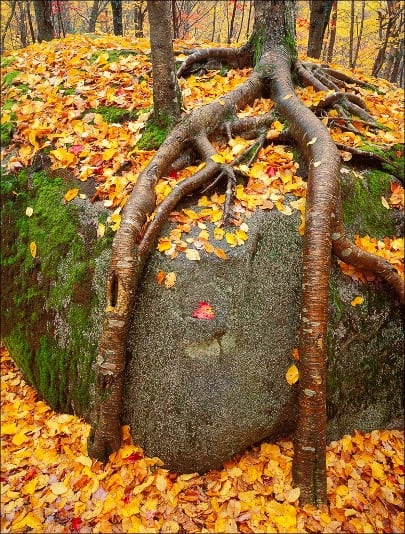

One photograph of mine, shown here, has assumed a position among my select tree photographs. As is often the case for me, the process of creating this image began with discovery and a sense of wonder. The roots of these trees thoroughly amazed me with their grace and determination! My judgment of the image relies on the overall technical quality; that I feel the image is as good as my best tree photographs; and that the image reconnects me with the sublime experience of being there.

Once you have explored a theme in depth, and hopefully you have seen your own vision of the subject grow and coalesce, you will probably find other themes in your work to cultivate into new portfolios. I am constantly thinking about themes in my own body of work to develop! Creative thinking along these lines may lead you to themes, evolving from your own personal passions that are yet unexplored by other photographers. The potential for rewards in terms of personal satisfaction, in the refinement of your presentation, and for marketing your work are increased. The first level of creativity comes with the image-making, but the next phase comes with the editing and organization of images in ways that reflect the photographer’s unique style and perspective.

Find your passion, develop depth, edit tightly! Simply put: focus!

It is the photographer’s task to explore, photograph, and share with others the multitude of interesting aspects in our world and our lives. We expose to others what we see, that which they might otherwise miss. What a joyful job!

To summarize, here are some suggestions and conclusions:

- Pick a theme about which you feel passionate, and that shows off your personal vision. When you begin looking through your images, consider both the technical and emotional qualities. Try to judge each photograph’s merits relative to the other selections within the theme so that the collective group is of equal, or near equal, quality.

- Work at tightening up a theme you select to create a balanced group and by refining the visual themes. For example, if you select to make a portfolio entitled Water, balancing your edit might include photographs showing the many ways we see water in nature. Your photographs could include ones of ice, mist, waterfalls, surf, reflections, blurred water from long exposures, water frozen by fast shutter speeds, etc. Too many of one type of water image might give an unbalanced effect. If you find gaps in your interpretation of your theme, assign yourself to make new images to fill the gaps.

- Titling your portfolio may well help you define what the images are about. Like giving a title to a book, the name you give to your theme will be critical to how viewers think about the images within. It is also an opportunity to be more poetic than descriptive. If “Water” as a title sounds too simple or boring, try something more creative like, “The Art of Water,” or “Water: Cycle of Life.”

I hope my ideas help you along the way of improving your photography and communicating the themes about which you are most passionate.

Online Mentoring – 4 Week Portfolio Development Course

“For more than two decades, William Neill has been offering his thoughts and insights about photography and the beauty of nature in essays that cover the techniques, business, and spirit of his photographic life. Curated and collected here for the first time, these essays are both pragmatic and profound, offering readers an intimate look behind the scenes at Neill’s creative process behind individual photographs as well as a discussion of the larger and more foundational topics that are key to his philosophy and approach to work.”

William Neill

His work was chosen to illustrate two special edition books published by The Nature Company, Rachel Carson’s The Sense of Wonder, and John Fowles’s The Tree. His photographs were also published in a three-book series on the art and science of natural process in collaboration with the Exploratorium Museum of San Francisco: By Nature’s Design (Exploratorium / Chronicle Books, 1993), The Color of Nature (Exploratorium/Chronicle Books, 1996) and Traces of Time (Chronicle Books/Exploratorium, Fall 2000). A portfolio of his Yosemite photographs has been published entitled Yosemite: The Promise of Wildness (Yosemite Association, 1994) for which he received The Director’s Award from the National Park Service. A monograph of his landscape photography entitled Landscapes Of The Spirit (Bulfinch Press/Little, Brown, 1997) relates his beliefs in the healing power of nature. Neill’s most recent book, William Neill–Photographer, A Retrospective (Triplekite Publishing, 2017) is a collection of his photographs taken over the past forty years. His latest book is Light on the Landscape (Rocky Nook, 2020), a collection of essays and images from his On Landscape column for Outdoor Photographer magazine.